6. Light and colour

Table of contents

Light

In specimen photography it is essential to have a consistent source and level of light. Each image should be taken under the same lighting conditions. This allows comparisons to be made between images as all light is standardised.

There are broadly three attributes that need to be considered when you are specifying lighting. These are:

1) Intensity 2) Colour temperature 3) Quality

Intensity is the most obvious of these, we need enough light to see what we are doing. However from a conservation point of view, for many objects light causes cumulative and irreparable damage such as fading and embrittlement. This is why most museums and art galleries employ subdued lighting, and window blinds. Many conservation manuals suggest a general light level of 200 lux. Light is measured in lumens and lux, but these units are generally not used in photography. You can read more useful background here

For photography, we will generally use light that is brighter than normal display conditions, but this is acceptable as the duration of exposure to this level of light will be very short. It therefore follows that you should not leave objects under bright lights for longer than needed - use a dummy object to perfect your setup and make the switch at the last moment. If you are particularly concerned about any objects, consult your conservator.

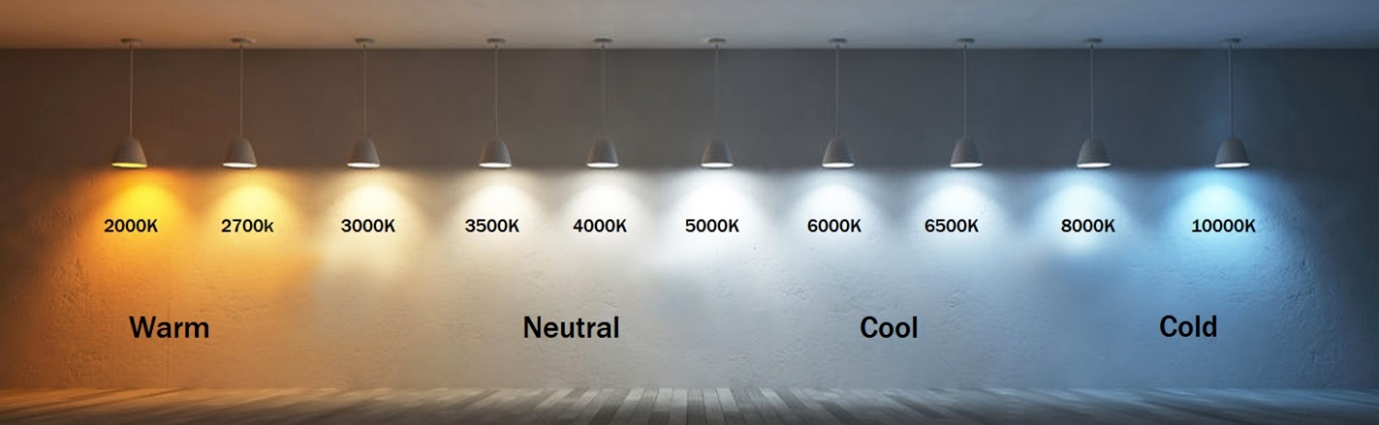

Colour temperature controls how warm or cold the light feels. Contrast the cold clinical lights in a lab or hospital to the cosy, warm atmosphere of a country pub with candles and a log fire. The colour temperature of overcast daylight, although somewhat variable, is often held up as being “neutral” and is what human eyes are used to seeing.

The colour temperature can affect the appearance of the specimen image. Imaging set ups should use a neutral Kelvin level that maintains accurate colouration as much as possible while also being well lit and bright. Something in the region of 4000 to 5500 is ideal. Kelvin can be measured using either a spectrometer (often very expensive), or alternatively this is usually stated on lightbulbs. It is also possible to get a measure of Kelvin from the camera itself.

Figure 1: Illustration of the Kelvin scale. Lower Kelvin values produce warmer/yellower light, whereas higher Kelvin values produce colder/bluer light. Image adapted from LEDlightingwholesaleinc.com.

Figure 1: Illustration of the Kelvin scale. Lower Kelvin values produce warmer/yellower light, whereas higher Kelvin values produce colder/bluer light. Image adapted from LEDlightingwholesaleinc.com.

Sources of ambient light - lighting in the studio, coming in through the windows - will cause a condition known as “mixed lighting” and will change the colour correctness of the image. Unless you are using strobes/flash, all of that will matter. Camera rigs and light boxes that can help remove sources of ambient light are an excellent way to get consistent light levels in images.

A good way to check if you have mixed lighting is to take two photos, camera settings locked, one lights on, other lights off. Ideally the lights on image are properly exposed, the lights off image should be as close to black as possible.

Light quality is less commonly known about but is dependent on the spectral power distribution of a light source. You can read more here, but to use an audio analogy, imagine going to hear your favourite band live, but the bass player has forgotten to turn their amplifier on - what you hear is a poor rendition because a part of the audio spectrum is missing. In photography, light quality is encapsulated in a value referred to as Colour Rendering Index, or CRI - you will find this value in the technical datasheets issued by lighting manufacturers. Images taken under low-CRI light will lack subtle differentiation between tones, e.g. between dark navy blue and black. For photography use, you should aim for a CRI of at least 90.

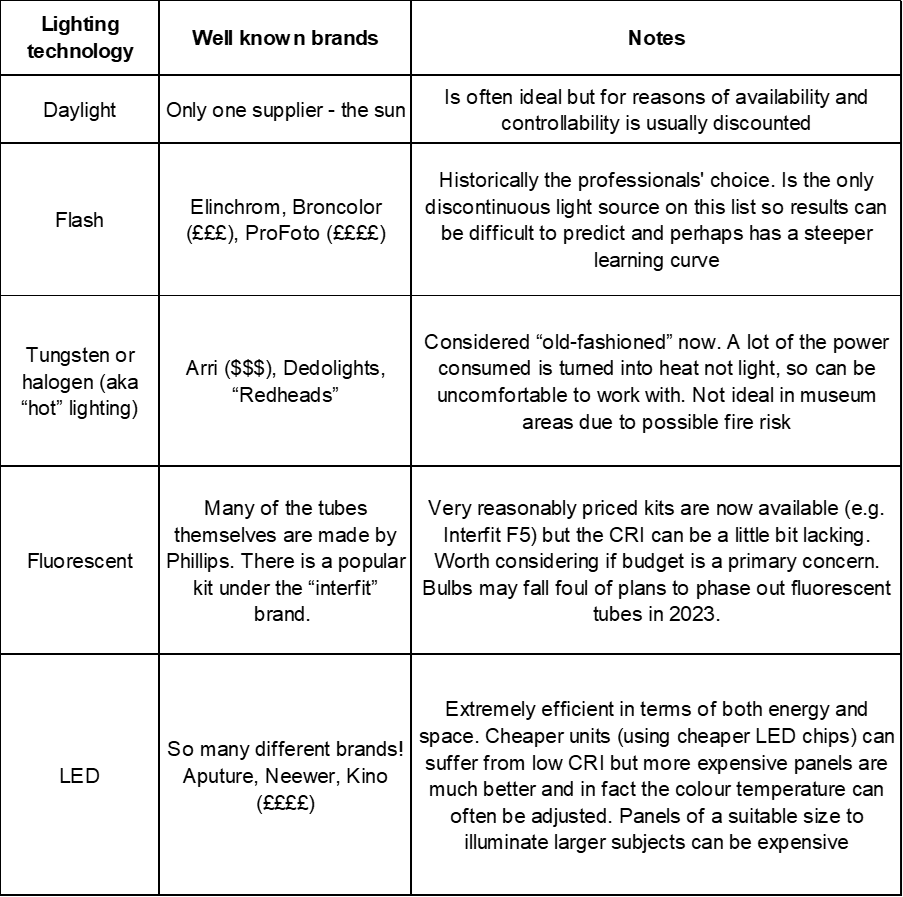

Which lights should you buy?

This is a complex and sometimes contentious issue, as there are so many issues to consider - but as long as your light meets the criteria outlined at the start of this section, there are a number of choices you could make. In recent years there has been significant crossover between the sectors of photography and cinematography, and as a result, many light types can now be considered as “dual-purpose”.

Colour and white balance

The previous section raises one of the key issues with digital photography – light affects image colour and is inconsistent. Light affects the colour, as does the camera, and the screen on which an image is viewed. This is a serious problem for digitisation efforts as we wish to capture specimens in the most accurate way possible and in a way that is comparable between specimens, cameras, set ups, and other collections.

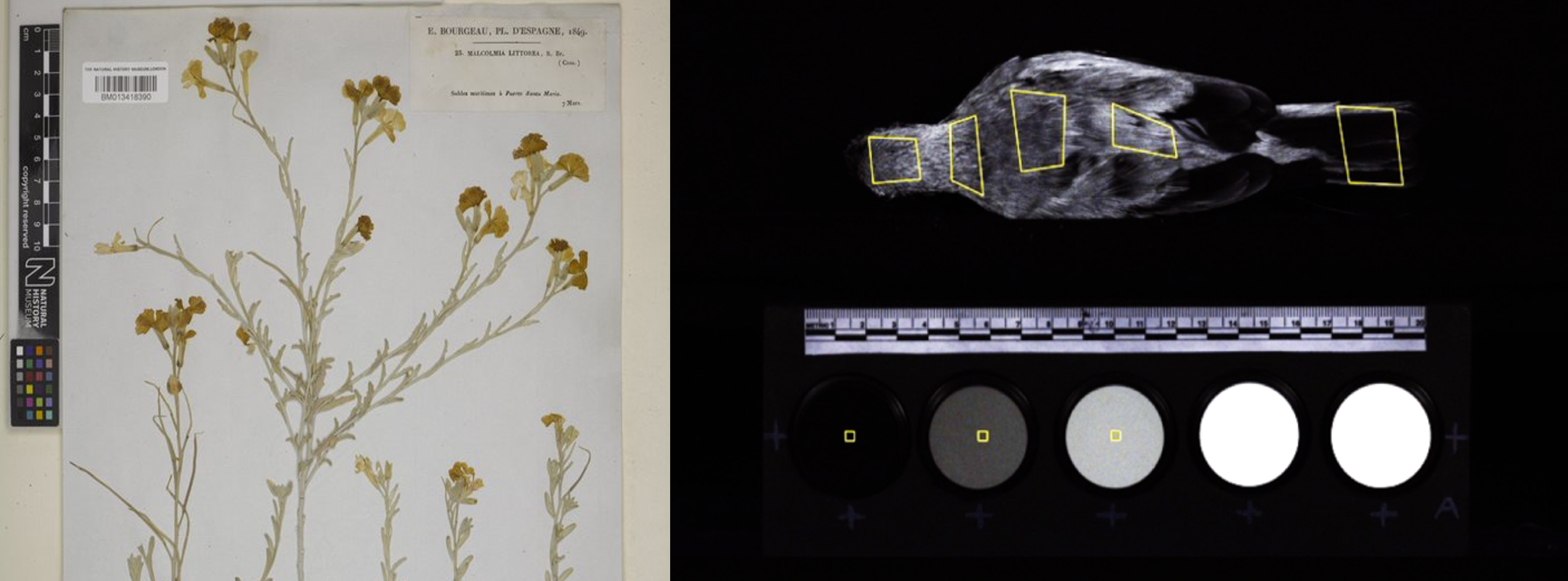

The solution to this is to use colour standards or a white balance chart to calibrate images. These are composed of spots of colour or white/grey scale shade that have specific reflective ranges. Colour/brightness is observed when different wavelengths of light are reflected by an image. Standards which reflect certain wavelengths and quantities can be used to correctly colour images by comparison. Digitally displayed colours can be described using several predefined systems such as a colours RAL (link of description) or a hex number which is unique to a specific colour and shade. The colour and whiteness of an image can be corrected on the computer when these values are known for included standards.

Standards can simply be a white/grey scale used to control the brightness or reflectance of an image while other are larger palettes with a range of colours. These are more useful when colour is an aim of the specimen’s image capture:

Figure 2: Examples of colour palates used in specimen photography. The left-hand image is a close up of the palette used in herbarium sheet photography at the NHM and used several colours and shades. The right-hand image shows an example from Cooney et al. 2019 where only grey-scale standards are used.

Figure 2: Examples of colour palates used in specimen photography. The left-hand image is a close up of the palette used in herbarium sheet photography at the NHM and used several colours and shades. The right-hand image shows an example from Cooney et al. 2019 where only grey-scale standards are used.

Palettes and standards can be bought online and are a standard feature in photography. Prices generally range between £50 and £100 which may seem a bit steep for what seems like a bit of card, but they are important to produce quality and comparable digital images of specimens.

Next page: 7. Photography setups